RL Blogs

By Ralph Laurel

Mar 30, 2013“Learning from the past means recognizing mistakes, resolving them to the best of your ability, and consciously deciding not to repeat them.” |

||

|

Galveston Bay) had seen 23 fatalities in the previous 30 years prior to the 2005 incident. In 2004 there were three major accidents with two involving fatalities, but the refinery achieved its lowest ever recordable injury rate.

Lack of Leadership – The Chemical Safety Board noted a poor safety culture in its investigation. The refinery leadership applied pressure to increase production. Production and budget compliance were found to be rewarded above everything else. In addition, there was a very high turnover rate in the leadership team. This resulted in a lack of ownership for issues that did not have immediate payouts.

Maintenance and operating procedures were inadequate, safety studies were years overdue, and hazard analysis was poor. Site leadership let the standards slip and didn’t prioritize Process Safety.

3/23 - Several units at the refinery were shutdown for maintenance activities. Ten trailers servicing the Ultracracker unit were located near the Isomerization unit, which was about to commence startup activities. None of the workers in the trailer were warned that the Isom unit was about to start up.

Unit not Cleared During Startup – The workers in the nearby trailers were not even aware of the startup activities right next to them. Startup and shutdown activities in a refinery are periods of highest danger and all non-essential personnel should be cleared from the unit.

2:15 am - Night shift began introducing raffinate to the Splitter tower. Level indication on the tower had a maximum range at 9 ft elevation. The tower was filled above the 9 ft mark due to concerns with damaging the furnace from low level. A high level alarm activated but second high level at higher elevation failed to trigger.

Procedure Deviations – Operators consciously deviated from startup procedures by over-filling the tower. This step was routinely not followed and an informal procedure had been adopted due to fears of losing level and liquid flow to heater. In general operating procedures were found to be out of date.

3:30 am – Feed to tower was stopped with an actual liquid level of 13 ft while the level indication showed 100%.

5:00 am – The lead operator updated the board operator on the status of unit operations in the control room and left an hour before end of his shift.

6:00 am – A new board operator arrived to start his 30th straight shift. He made a brief shift relief and read the logbook. There was no mention of the liquid level in the Splitter tower.

7:15 am – The day shift supervisor arrived late and received no briefing on status of unit.

Shift Relief – There were limited communications between night shift and day shift on tower level and no face to face shift relief between night and day shift occurred. The communication in the written logbook was incomplete. Quality shift relief is essential in managing safe and reliable unit operations, especially during abnormal operations.

9:51 am – The unit startup resumed. Liquid was recirculated and more feed was added to the tower. The procedure called for regulating liquid level with a control valve but valve was left closed. This caused the level in the tower to build further.

Tower Level Control – Operator didn’t scrutinize the mass balance on the tower. With liquid going into the tower but nothing coming out, the mass balance would indicate accumulation in the tower. Yet the operator continued with the level control valve closed.

Operator Training – The operators were not aware of the hazards associated with tower overfilling. BP had transitioned to computer based training instead of face to face training. Simulators were also not implemented at the site due to initial investment.

10:00 am – Burners were lit in the associated furnace, increasing the temperature in the tower.

11:00 am – The Day Supervisor left refinery to attend to family medical emergency. No experienced supervisor was appointed to replace him.

Human Factors - second operator position eliminated in 1999

12:00 pm – Liquid level in the tower reached 98 ft but the improperly calibrated level showed height of 8 ft and slowly falling.

Poorly Functioning Instrumentation - Operator relied on the tower level reading that indicated that level was declining. The calibration of the level indication was based on 1975 data for a different process liquid. The sight glass on the tower was also dirty and couldn’t be used to verify level. The high level alarm had also failed to activate.

Worker Fatigue – The operator’s judgement was potentially impaired due to fatigue. He fixated on one operating parameter (decreasing level) and lost sight of other indications. He had been on 12 hr shifts for the prior 29 days and had experienced acute sleep loss. The Texas City refinery had no fatigue management policy.

12:41 pm – An alarm activated for high pressure in the Splitter. A vent to the blowdown drum was opened and two burners in the furnace were turned off. The flow out of the tower was also opened up to storage. This flow was routed through feed/effluent exchangers, which caused the temperature of the feed to the tower to increase by 140 deg F

1:00 pm – Contractors returned from lunch and began a meeting at the trailer closest to the blowdown drum.

Blast Proof Shelters – The contractor trailers were placed based on convenience and not safety. The shelters were placed too close to process equipment (120 ft from blowdown drum). During an explosion, it is safer to be in an open atomosphere than a weak structure. The force from a blast can destroy a weak trailer, causing walls to collapse and creating shrapnel in the process. In addition, the placement of the temporary trailers did not follow a management of change procedure.

The tower liquid began boiling due to increase in feed temperature. The level in the tower reached the top and liquid began spilling into the overhead vapor lines. The high pressure caused the relief valves to open and relieve to the nearby blowdown drum. As the blowdown drum began to fill liquid spilled to the process sewer from the drum and set off alarms. The high level alarm in blowdown drum failed to trigger.

Lack of Proper Maintenance – Numerous work orders had been written to address this high level alarm but were closed without the work being completed.

Budget Cuts – There had been a failure to invest at the site for many years. Numerous arbitrary across the board cuts were implemented without understanding the potential impacts.

The blowdown drum overfilled and a geyser of hot flammable liquid sprayed out of the stack. The liquid spilled out on ground and formed a vapor cloud that expanded in 90 seconds, engulfing the unit and nearby trailers.

Atmospheric Relief – Atmospheric reliefs for hydrocarbon streams are inherently dangerous. These streams should be routed to a safer location such as a flare where possible. BP considered a connection to the flare and replacing the blowdown stack but numerous proposals were rejected due to the high cost.

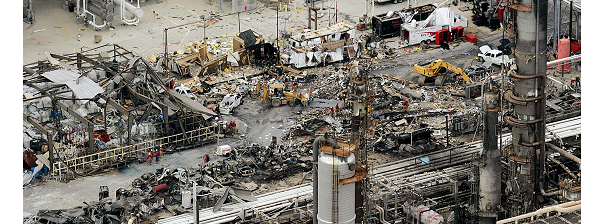

25 ft from the drum, an idled pickup truck ignited the vapor cloud and triggered the explosion. The explosion resulted in heavy destruction and ignited fires which lasted for hours. The trailers nearby were completely destroyed by the blast and 15 workers were killed. The Isom unit remained shut down for more than 2 years.

Within the modern refining industry, the BP Texas City incident marked an unforgettable event. We have all read through the incident reports numerous times over the years, but as each year passes, we become slightly desensitized to the tragedy that occurred.

I write this article on the anniversary of the event in hopes of re-emphasizing the focus around personnel and process safety. Nobody's life is worth an extra penny earned for any company, so we should all constantly focus on learning from the past to improve the future of our employees, community, and environment. | ||

|

|